Intended audience

The brief is intended for stakeholders engaged in arguing for biodiversity as well as policy makers wishing to explain or justify why particular biodiversity protection decisions are made.

Topic

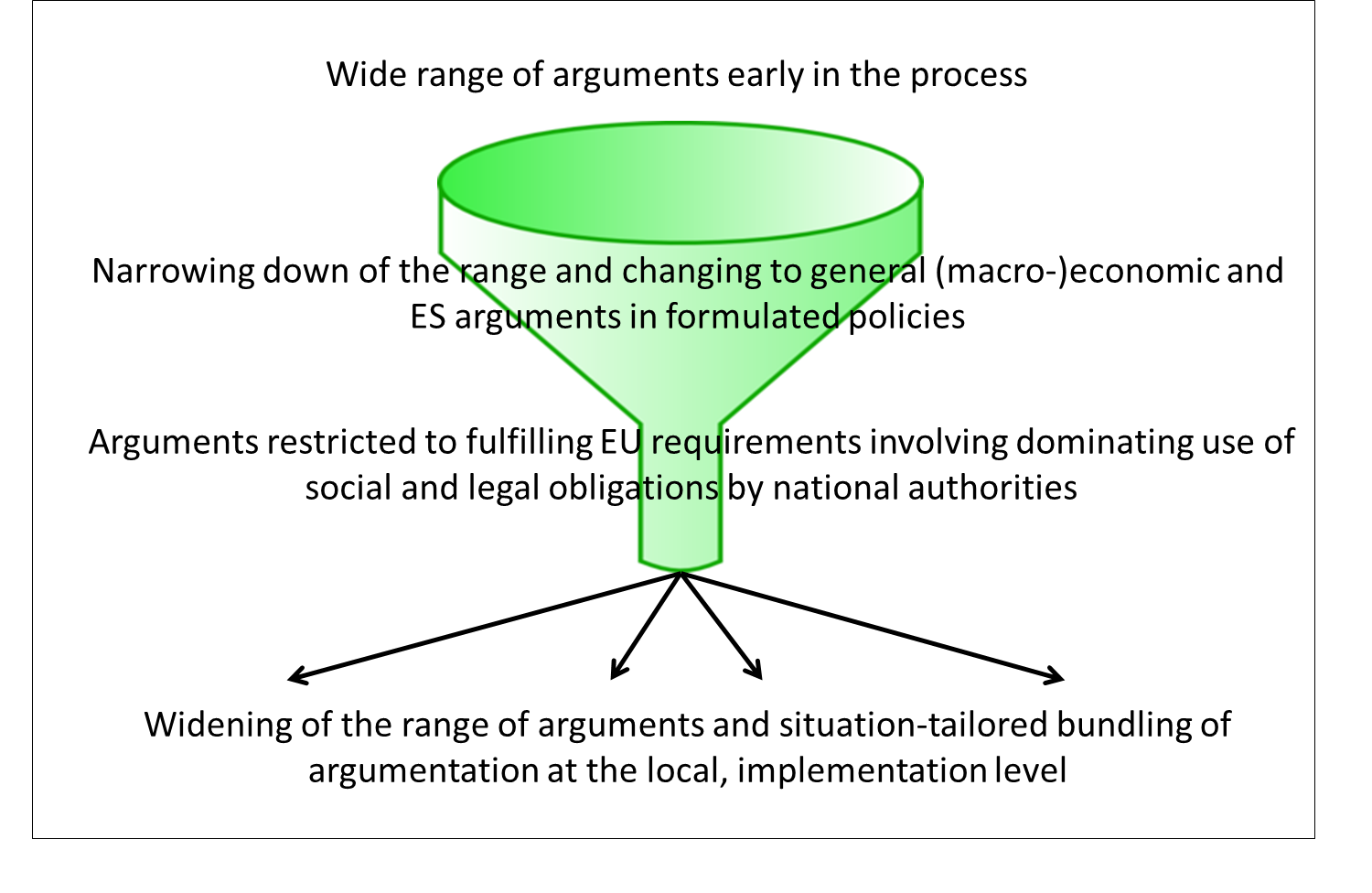

One of the general conclusions from the BESAFE case studies is that it is frequently beneficial to use combinations of arguments together in a “bundle” when seeking support for biodiversity conservation. We found that a larger variety of arguments being used together in a bundle tends to increase the overall effectiveness of argumentation, particularly in situations where a larger number of parties is involved in the decision making process. For example, in both the Dutch and Hungarian Natura 2000 case studies, the single argument of legal obligation was effective in achieving progress during the national level policy adoption and initial implementation stages of the policy cycle, but this was insufficient at the practical implementation level where further arguments were required to obtain the support of additional local and regional stakeholders (see deliverable D3.1 and the Dutch and Hungarian case study briefs).

Consultations with stakeholders during BESAFE workshops strongly endorsed this finding. The stakeholders shared the opinion that arguments in isolation are often weak because different actors react differently to different arguments, and because any individual may need a number of arguments, or repetitions of arguments, to be convinced of anything that goes against their own initial preconceptions. Argumentation will often be most effective when it is relevant for many actors, used along with other arguments timeously, repeatedly, and in fitting with the contextual situation (see deliverables D2.2 and D5.1).

Thus bundling different arguments together tends to increase their overall effectiveness, particularly at stages in a deliberation process where the support of multiple users is needed and where a consensus needs to be reached. Examination of the Dutch Natura 2000 case study in a little more detail, for instance, reveals that the use of the particular argument of legal obligation in the early stages of national adaptation and implementation of European policy was very effective and efficient. However, this use of legal power alienated stakeholders who were needed later in the process, at the practical implementation stage. Convincing them by introducing a bundle of further appropriate arguments then required extra time, but proved to be a successful argumentation strategy (Figure 1 and see deliverable D2.3).

Usefulness

The BESAFE case studies provide evidence that bundling arguments together is useful in at least two types of situations. The first is where arguments simply reinforce each other. We found that logical, scientific arguments needed to be backed up by arguments that related to responsibility or duty, such as moral nature value or legal obligation, or to benefits, such as local livelihood or recreation. In the Białowieża forest case study for example, the logical, solid evidence based argument on the detrimental impact of forestry on forest biodiversity was only effective when supported by strong legal argumentation (see deliverable D2.3 and the Białowieża case study brief).

The second general situation where bundling is useful is where it facilitates a gain in knowledge and understanding shared between the different actors involved in the process. Often, arguments that some actors were previously not aware of or did not appreciate, can allow them to see different values, or make them aware of synergies or trade-offs, or allow them to appreciate the value of biodiversity for others. The BESAFE case studies provide examples of such situations, frequently in circumstances where arguments originally brought in by one party are understood and taken up by other parties with a gain in momentum (see deliverable D2.3).

This is clearly apparent in arguments expressed by local inhabitants in relation to their livelihoods. For example, the cultural values of livestock practices originally held by shepherds and other animal keepers gradually entered mainstream thinking on protected areas management in the Andalusia case study. In the case of fox and wild boar comebacks in Belgium, the damage inflicted by these animals on farming and local communities was further used as a main argument by political parties, the farmer union and even the hunting association to advocate for legislation change. Similarly, livelihood concerns on the costs of potential National park enlargement for local people in the Polish Białowieża forest case, initially expressed by local communities were with time taken up by the environmentalists and national level decision makers. In the Danube catchment case study, rights of nature and balance in nature arguments diffused from academic debates to be taken up in mainstream planning (see deliverables D2.3 and D3.1 and the Fox and Wild Boar (Belgium), Białowieża (Poland) and Danube catchment (Rumania) case study briefs). All of these examples indicate that the inclusion of bundles of arguments can facilitate a spread of understanding across stakeholder groups that allows a general consensus to be reached in the decision-making process.

Transferability

The general usefulness of bundling applies to most situations. Because different people are sensitive to different arguments, bundling arguments most obviously applies to situations where there is real deliberation between multiple parties holding different views. But as most people are sensitive to more than one argument, bundles also can apply to situations where just one individual needs to be convinced. Although bundling would not seem to particularly apply to a situation where one dominant argument is used to force a decision, as is set out in the previous section even there it could be sensible and eventually useful to use argument bundles increase understanding and decrease irritation, as an investment for a smoother process in consecutive stages.

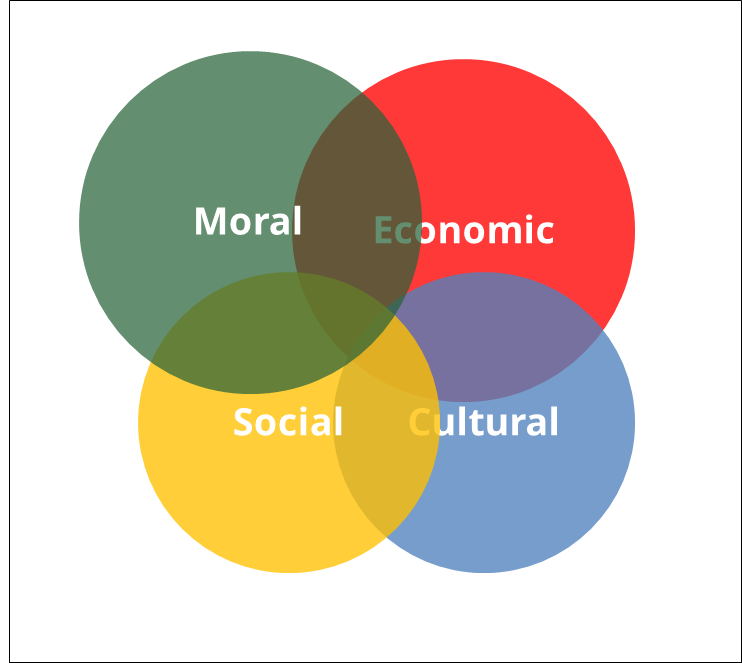

Another generally transferable aspect is in the mix of types of arguments. Bundles may incorporate arguments that take different lines, including both moral and economic values, which vary considerably in importance for different stakeholders, as demonstrated by BESAFE studies of stakeholder viewpoints (see the Q studies of stakeholder viewpoints reported in deliverable D4.1 part II). The results of these studies indicate that one way to improve biodiversity protection is to ensure a better balance between such argument types rather than assuming that, for example, decision-makers will only respond to financial arguments (see deliverable D4.1-Synthesis).

Lessons learned

- Bundling arguments directly increases effectiveness at stages where there is real deliberation between multiple stakeholders.

- Using argument bundles at stages of the argumentation process where there is no (functional) deliberation, may still improve effectiveness and process efficiency overall.

- Using argument bundles shows people new angles, synergies and trade-offs and in general facilitates deliberation.

- In particular bundling moral and economic (livelihood) arguments can increase the effectiveness of conservation.

- Ensuring a better balance between several lines of argumentation instead of making selections based on assumed effectiveness beforehand may be key to improving biodiversity protection.

Looking for more information on effective arguments for biodiversity?

For more BESAFE results, including separate briefs focusing on other case studies and various aspects of argumentation, see http://www.besafe.pensoft.net

Results referred to in this brief can be found in the BESAFE deliverables D2.2, D2.3, D3.1 and D4.1 part II, D4.1 Synthesis and D5.1. All BESAFE deliverables are available from http://www.besafe.pensoft.net/deliverables.php?P=4&SP=32

This brief is a result of research carried out under the BESAFE project. This brief was written by Rob Bugter. Further information is available at tool-besafe.pensoft.net

The BESAFE project is an interdisciplinary research project funded under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme, contract number: 282743.